Edward Snowden’s Strangely Free Life – As a Robot

He <span class="message_body">is an exile like no other, able to slip the bonds of his banishment on wheels.</span>

Edward Snowden lay on his back in the rear of a Ford Escape, hidden from view and momentarily unconscious, as I drove him to the Whitney museum one recent morning to meet some friends from the art world. Along West Street, clotted with traffic near the memorial pools of the World Trade Center, a computerized voice from my iPhone issued directions via the GPS satellites above. Snowden’s lawyer, Ben Wizner of the American Civil Liberties Union, was sitting shotgun, chattily recapping his client’s recent activities. For a fugitive wanted by the FBI for revealing classified spying programs who lives in an undisclosed location in Russia, Snowden was managing to maintain a rather busy schedule around Manhattan.

A couple nights earlier, at the New York Times building, Wizner had watched Snowden trounce Fareed Zakaria in a public debate over computer encryption. “He did Tribeca,” the lawyer added, referring to a surprise appearance at the film festival, where Snowden had drawn gasps as he crossed the stage at an event called the Disruptive Innovation Awards. Wizner stopped himself mid-sentence, laughing at the absurdity of his pronoun choice: “He!” Behind us, Snowden stared blankly upward, his face bouncing beneath a sheet of Bubble Wrap as the car rattled over the cobblestones of the Meatpacking District.

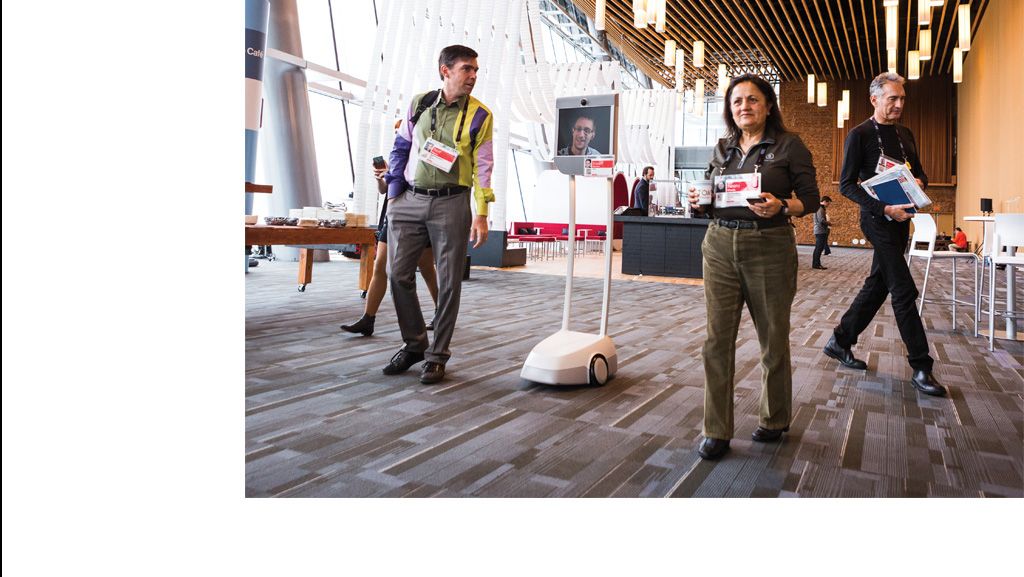

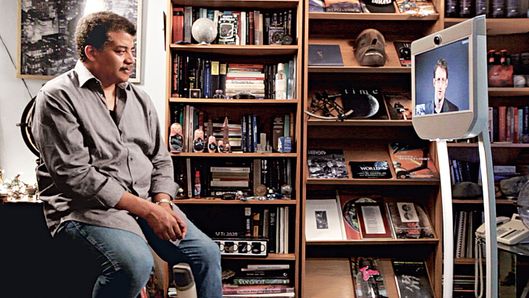

Snowden’s body might be confined to Moscow, but the former NSA computer specialist has hacked a work-around: a robot. If he wants to make his physical presence felt in the United States, he can connect to a wheeled contraption called a BeamPro, a flat-screen monitor that stands atop a pair of legs, five-foot-two in all, with a camera that acts as a swiveling Cyclops eye. Inevitably, people call it the “Snowbot.” The avatar resides at the Manhattan offices of the ACLU, where it takes meetings and occasionally travels to speaking engagements. (You can Google pictures of the Snowbot posing with Sergey Brin at TED.) Undeniably, it’s a gimmick: a tool in the campaign to advance Snowden’s cause — and his case for clemency — by building his cultural and intellectual celebrity. But the technology is of real symbolic and practical use to Snowden, who hopes to prove that the internet can overcome the power of governments, the strictures of exile, and isolation. It all amounts to an unprecedented act of defiance, a genuine enemy of the state carousing in plain view.

We unloaded the Snowbot in front of the Whitney, where a small group had gathered to meet us for a private viewing of a multimedia exhibition by the filmmaker Laura Poitras. It was Poitras whom Snowden first contacted, anonymously, in 2013, referring to the existence of a surveillance system “whose reach is unlimited but whose safeguards are not.” Their relationship resulted in explosive news articles and a documentary, Citizenfour — work that won a Pulitzer and an Oscar and incited global outrage. But the disclosures came at a high price for their source. If Snowden couldn’t come home, Poitras at least wanted him to share vicariously in the experience of her Whitney show, “Astro Noise,” which took its name from an encrypted file of documents he had spirited out of the secret NSA site where he worked in Hawaii. So she had arranged a personal tour.

Outside an eighth-floor gallery, a crowd of Poitras’s collaborators and Whitney curators clustered around the Snowbot as a white circle twirled on its monitor. Then, suddenly, the screen awoke and Snowden was there.

“Hey!” Wizner said, and the group erupted in awkward laughter. The famous fugitive was wearing a gray T-shirt, his face pallid and unshaven. (He calls himself “an indoor cat.”) His voice sounded choppy, but some fiddling resolved the problem, and Poitras, soft-spoken and clad in black, made introductions. Snowden’s preternaturally eloquent Hong Kong hotel-room encounter with Poitras and the Guardian journalists investigating his leaks formed the core of Citizenfour, but even some of those who worked on the documentary had never met its protagonist. One of the cinematographers came forward and wrapped him in a hug.

“I don’t have hands,” Snowden apologized. “The most I can do is maybe …”

He scooted forward.

Sitting in the same homemade studio he uses for his frequent speaking engagements, Snowden could control the robot’s movements with his computer, maneuvering with uncanny agility, swiveling to make eye contact with people as they spoke to him.

Poitras began with the show’s opening piece, a colorful array of prints that resembled modern abstracts but were actually found objects: visualizations of intercepted satellite signals that turned up in the vast trove of NSA documents. “The whole show, there’s a lot of deep research that’s going on behind it,” she said. She led Snowden into a darkened gallery, where a spooky ambient soundscape was playing over video footage of a U.S. military interrogation. Momentarily disoriented, he careened into a bench. But Snowden quickly figured out how to navigate in the dark. When he came to parts of the exhibit that required complicated movements — lying on a platform to take in the watchful night sky over Yemen, or craning to look at an NSA document through a slit in the wall — the humans hoisted him into position.

“Wow, okay, I see it,” Snowden said as one of Poitras’s researchers held him up to view footage of a drone strike’s aftermath. “This is a surreal experience for a number of reasons.”

When the tour was over, Snowden held an impromptu discussion, likening his decision to become a dissident to a risky artistic choice. “There’s always that moment where you step out and there’s nothing underneath you,” he said. “You hope that you can build that airplane on the way down, or if you don’t, that the world will catch you. In my case, I’ve been falling ever since.” Still, Snowden said he had no regrets. “I do have to say,” he told Poitras, “that I will be forever grateful that you took me seriously.”

As usual, though, when the questions turned to the details of his non-robotic existence, Snowden remained courteously evasive. “What’s a day in the life now?” asked Nicholas Holmes, the Whitney’s general counsel. “Do you go for walks in the park?”

“Well,” the Snowbot replied, “I go for walks in the Whitney, apparently.”

Watch the Snowbot's visit to New York's office.

The idea that Snowden is still walking the American streets, virtually or otherwise, is infuriating to his former employers in the U.S.-intelligence community. Its leaders no longer make ominous jokes about wanting to put him on a drone kill list — as former NSA and CIA director Michael Hayden did in 2013 — but they still vilify him and maintain that he did real harm to America’s safety and international standing. While Snowden’s leaks revealed the NSA’s controversial and possibly unconstitutional bulk collection of domestic internet traffic and telephone metadata, they also exposed technical details about many other classified activities, including overseas surveillance programs, secret diplomatic arrangements, and operations targeting legitimate adversaries. The spy agencies warn that the public doesn’t comprehend the degree of damage done to their protective capabilities, even as events like the Orlando nightclub massacre demonstrate the destructive reach of terrorist ideology. The fallout from Snowden’s actions may have prompted a debate about security and privacy that even President Obama acknowledges “will make us stronger,” but there has been no such reassessment, at least officially, of Snowden himself. He still faces charges of violating the federal Espionage Act, crimes that could carry a decades-long prison sentence.

When Snowden first revealed the NSA’s surveillance — and his own identity — to the world three years ago this month, there was little reason to believe that he would be in a position to communicate much of anything in the future. The last person to leak classified information of such magnitude, Chelsea Manning, was sentenced to 35 years in prison. (Manning, who was held in solitary confinement while awaiting trial, has largely communicated to the public through letters.) Yet so far, to his own surprise, Snowden has managed to avoid the long arm of U.S. law enforcement by finding asylum in Russia. Leaving aside, at least for the moment, the ethics of his actions (and the internal contradictions of his residence in an authoritarian state ruled by a former KGB operative), Snowden’s case is, in fact, a study in the boundless freedoms the internet enables. It has allowed him to become a champion of civil liberties and an adviser to the tech community — which has lately become radicalized against surveillance — and, in the process, the world’s most famous privacy advocate. After he appeared on Twitter last September — his first message was “Can you hear me now?” — he quickly amassed some two million followers.

“I feel like we’re sort of dancing around the leadership conversation,” Snowden said to me recently as I sat with him at the ACLU offices. Over the past few months, we have encountered one another with some regularity, and while I can’t claim to know him as a flesh-and-blood person, I’ve seen his intellect in its native habitat. He is at once exhaustively loquacious and reflexively self-protective, prone to hide behind smooth oratory. But occasionally, he has let down his guard and talked like a human being. “I’m able to actually have influence on the issues that I care about, the same influence I didn’t have when I was sitting at the NSA,” Snowden told me. He claims that many of his former colleagues would agree that the programs he exposed were wrongfully intrusive. “But they have no voice, they have no clout,” he said. “One of the weirder things that’s come out of this is the fact that I can actually occupy that role.” Even as the White House and the intelligence chiefs brand him a criminal, he says, they are constantly forced to contend with his opinions. “They’re saying they still don’t like me — tut-tut, very bad — but they recognize that it was the right decision, that the public should have known about this.”

Needless to say, it is initially disorienting to hear messages of usurpation emitted, with a touch of Daft Punk–ish reverb, from a $14,000 piece of electronic equipment. Upon meeting the Snowbot, people tend to become flustered — there he is, that face you know, looking at you. That feeling, familiar to anyone who’s spotted a celebrity in a coffee shop, is all the more strange when the celebrity is supposed to be banished to the other end of the Earth. And yet he is here, occupying the same physical space. The technology of “telepresence” feels different from talking to a computer screen; somehow, the fact that Snowden is standing in front of you, looking straight into your eyes, renders the experience less like enhanced telephoning and more like primitive teleporting. Snowden sometimes tries to put people at ease by joking about his limitations, saying humans have nothing to fear from robots so long as we have stairs and Wi-Fi dead zones in elevators. Still, he is quite good at maneuvering on level ground, controlling the robot’s movements with his keyboard like a gamer playing Minecraft. The eye contact, however, is an illusion—Snowden has learned to look straight into his computer’s camera instead of focusing on the faces on his screen.

Here’s the really odd thing, though: After a while, you stop noticing that he is a robot, just as you have learned to forget that the disembodied voice at your ear is a phone. Snowden sees this all the time, whether he is talking to audiences in auditoriums or holding meetings via videoconference. “There’s always that initial friction, that moment where everybody’s like, ‘Wow, this is crazy,’ but then it melts away,” Snowden told me, and after that, “regardless of the fact that the FBI has a field office in New York, I can be hanging out in New York museums.” The technology feels irresistible, inevitable. He’s the first robot I ever met; I doubt he’ll be the last.

Wizner, the head of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, says that Snowden asked him to do some research on telepresence in their first conversation, back when he was still very much on the lam. Now that his situation has stabilized — at least for the time being — he and Snowden’s small coterie of advisers are discussing ways they might use it for a widening range of purposes. Glenn Greenwald, one of Snowden’s original journalistic collaborators, jokingly talks about taking the Snowbot on the road. “I would love to let it loose in the parking lot of Fort Meade,” where the NSA is headquartered, he said. “Or to randomly go into grocery stores.” More seriously, Snowden’s advisers are in discussions about a research fellowship at a major American university. Already, the Snowbot has twice taken road trips to Princeton University, where he has participated in wide-ranging discussions about the NSA’s capabilities with a group of renowned academic computer-security experts, rolling up to cryptographers during coffee breaks and dutifully posing for selfies.

For larger gatherings, Snowden usually dispenses with the robot, addressing audiences from giant screens. (He often opens with an ironic reference to Big Brother.) He is scheduled to make more than 50 such appearances around the world this year, earning speaking fees that can reach more than $25,000 per appearance, though many speeches are pro bono. Besides allowing Snowden to make a good living, his virtual travels on the public-lecture circuit are part of a concerted campaign to situate him within a widening zone of political acceptability. “One of the things we were trying to do is to normalize him,” says Greenwald. “Normalize his life, normalize his presence.” In 2014, Snowden joined Poitras and Greenwald on the board of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, a San Francisco nonprofit, and last year he was elected chairman. It serves as a base for his advocacy and gives him access to a staff of technologists with whom he has been working on encryption projects, tools intended to allow journalists to communicate with “people that live in situations of threat” — in other words, people like Snowden himself.

Through a network of intermediaries — chief among them Wizner, who acts as his advocate, gatekeeper, and talent agent in the United States — Snowden is able to establish contact with almost anyone he desires to meet. “Ed’s now getting a lot of people on the phone, and it’s broadening his horizons,” says the author Ron Suskind, who has spoken with him on several occasions and recently had him lecture to a class he and Lawrence Lessig were teaching at Harvard Law School. Snowden also recently spoke to Amal Clooney’s law class at Columbia, starred in an episode of the Vice show on HBO, and published a manifesto on whistle-blowing on the Intercept, the website Poitras and Greenwald started with the billionaire Pierre Omidyar. And he has been maintaining his presence on Twitter, where he has been playfully talking up Oliver Stone’s forthcoming film, Snowden, which will star Joseph Gordon-Levitt.

The biopic’s September release date matches up with Wizner’s timetable for mobilizing a clemency appeal to Obama. “We’re going to make a very strong case between now and the end of this administration that this is one of those rare cases for which the pardon power exists,” Wizner said. “It’s not for when somebody didn’t break the law. It’s for when they did and there are extraordinary reasons for not enforcing the law against the person.” He says that while no single event is likely to shift opinion in Washington, Snowden’s activities work “in the aggregate” to further his cause.

One thing Snowden refuses to do, however, is apologize. If anything, the last three years have turned him more strident. Whereas he once espoused a fuzzy dorm-room libertarianism — “some of it was kind of rudimentary,” Greenwald recalls — today he offers a more traditional leftist critique of the “deep state.” On Twitter, he has been admiring of Bernie Sanders, acerbic about Hillary Clinton’s foreign policy, and bitingly sarcastic about her handling of classified emails. In February, he tweeted: “2016: a choice between Donald Trump and Goldman Sachs.” He sees himself as part of a hacktivist movement, and he took pride when the anonymous source behind the massive cache of offshore banking data known as the Panama Papers cited Snowden’s example. In his Intercept essay, he called such leaking “an act of resistance.”

WNYC recently staged a sold-out Friday-night event at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, not far from Fort Greene Park, where some artists surreptitiously erected a Snowden bust last year. At the appointed time, the fugitive appeared on a screen at the front of an ornate opera hall. It was around 2:30 a.m. in Moscow, but Snowden looked wide-awake, wearing an open-collared shirt and blazer and his customary stubble. “In an extraordinary and unpredictable way,” he told the audience, “my own circumstances show there is a model that ensures that even if we’re left without a state, we aren’t left without a voice.”

When Snowden went public, one of the first people he sought out was a historical antecedent: Daniel Ellsberg, the military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers. He, too, was briefly a fugitive and faced Espionage Act charges, until they were dropped because of the illegal retaliatory actions of President Nixon. Now 85, Ellsberg was eager to talk to Snowden and they connected over an encrypted chat program.

“I had the feeling that, as I suspected from the beginning, we really were kindred souls,” Ellsberg told me.

Ellsberg, mindful of Manning’s experience, advised Snowden to give up any thought of returning home. Snowden was inclined to agree. From the beginning, he had spoken fatalistically about the consequences of his actions. “All my options are bad,” Snowden acknowledged in his first interview in Hong Kong, which was published in the Guardian. If the American government didn’t grab him, the Chinese might, just to find out what he knew. He hinted that the CIA might even try to kill him, either directly or through an intermediary like a triad gang. “And that’s a fear I’ll live under for the rest of my life, however long that happens to be,” Snowden said at the time.

“He didn’t have a plan,” says Wizner. Snowden assumed that he would probably be silenced in one way or another, so he worked with a sympathetic programmer in the United States to design a website, supportonlinerights.com, which was to contain a letter addressed to the public. But instead, he more or less got away with it. After a nervy flight and an agonizing five-week wait in limbo at the Moscow airport, he was granted temporary asylum in Russia by President Vladimir Putin. Photos soon appeared in the Russian media showing Snowden pushing a grocery cart and looking slyly over his shoulder on a riverboat ride. It was an uneasy deliverance, though, one seemingly subject to Putin’s unpredictable geopolitical power considerations.

Snowden argues that he was put in Russia by the U.S. government, which canceled his passport while he was en route to Ecuador, trapping him in Moscow during a layover. But to critics, his dependence on Putin is discrediting. “I am not saying that he is a Russian spy, but he is in a tough spot,” says journalist Fred Kaplan, author of the recent book Dark Territory: The Secret History of Cyber War. “He is in a position where, because of his captive status, he can’t really say anything that terribly critical about his hosts, who happen to be some of the most sophisticated and intrusive cyberespionage hackers in the world.” Many in the intelligence community darkly speculate about the nature of Snowden’s accommodation with the FSB, the Russian security service, which is not renowned for its hospitality or respect for civil liberties.

Although Snowden acknowledges that he was approached by the FSB, he claims he has given them no information or assistance, and he vehemently denies he is anyone’s puppet. He cheered the release of the Panama Papers, which contained voluminous evidence of corruption in Putin’s inner circle. “I have called the Russian president a liar based on his statements on surveillance, in print, in the Guardian,” he said with an uncharacteristic flash of annoyance, when I asked whether he felt any constraints in discussing Russia. “I have criticized Russia’s laws on this, that, and the other. It’s just frustrating to get the question because it’s like, look, what do I have to do?”

Snowden seems determined to refute predictions that he would end up broken, like so many whistle-blowers before him, or drunk and disillusioned, like a stereotypical Cold War defector. (He has claimed that he drinks nothing but water.) “People think of Moscow as being hell on earth,” he said during his Whitney visit. “But when you’re actually there, you realize it’s not that much different than other European cities. Their politics are wildly different, and of course really they’re problematic in so many ways, but the normal people, they want the same things.” He says he does his own shopping and takes the metro. Family members come to visit. His longtime girlfriend, Lindsay Mills, reunited with him in Moscow and has posted Instagram snapshots of her life there.

Last year, before Halloween, Mills posted a Photoshopped picture that posed the couple in front of FBI headquarters, with Snowden costumed as the capped protagonist of Where’s Waldo? As improbable as it may sound, he has told confidants that he doesn’t think the U.S. government has managed to pin down his exact whereabouts. He says he has designed his new life around his unique “threat model,” minimizing his vulnerability to tracking by giving up modern conveniences like carrying a phone. “He does not believe that he’s shadowed all the time by the CIA,” says Ellsberg, who has been in regular contact. “But he does believe that he is in the sights of the FSB all the time, partly to keep him safe.” Snowden is most at ease when he’s on the internet, an environment he feels he can control. As a former systems engineer, he has been able to construct back-end protections that allow him to feel confident that he can evade locational detection, even when he is using the internet like a civilian. He has sometimes chatted via video on Google Hangouts.

Snowden is more wary about in-person meetings, typically conducting them in hotels like the Metropol near Red Square. More than a year after they began speaking, Ellsberg finally had the opportunity to meet Snowden in person, when he visited Moscow with an informal goodwill delegation that also included the actor John Cusack and the leftist Indian author Arundhati Roy. At the appointed time, Snowden called and said to meet him in the lobby of their hotel. Cusack took the elevator downstairs, and Snowden surprised him by getting on at the fourth floor. When they returned to the room, Ellsberg greeted Snowden by saying, “I’ve been waiting 40 years for someone like you.”

Two days of marathon bull sessions and room-service dining ensued. Ellsberg tried — unsuccessfully — to get confirmation of some long-held suspicions about the extent of the NSA’s spying on Americans. Periodically, Snowden would point to the ceiling, to remind the room that others were probably listening. Cusack and Roy later recounted the conversation in a 13,000-word essay, writing that when the meeting was over, Ellsberg lay down “on John’s bed, Christ-like, with his arms flung open, weeping for what the United States has turned into — a country whose ‘best people’ must either go to prison or into exile.”

The notion that Snowden has become, to some, a sort of mythic figure — the Oracle of the Metropol — is profoundly annoying to the people who actually hold the nation’s intelligence secrets. “I’d love to see him come back to the U.S. and take his medicine,” says Robert Litt, general counsel for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, who has been deeply involved in both the legislative fallout from the NSA revelations and internal government discussions over the potential prosecution of Snowden. Litt says he sees the consequences of Snowden’s actions on extremist message boards, which now exhort jihadis to use encryption. “It cannot be disputed,” he told me, “that this has had immeasurable impact.”

Snowden believes that officials like Litt are merely trying to scare the public into acquiescence. Last October, the two had a showdown of sorts when they spoke back-to-back at a conference at Bard College. “Each time we have an election, it’s like another round of a game,” Snowden told the students. Using a livecasting program designed for gamers that allows him to project illustrations, he filled the auditorium screen with an image of George W. Bush shaking hands with Obama. “The policies of one president become the policies of another.” Then he played a video clip of the cleric Anwar al-Awlaki’s son, a 16-year-old American citizen killed by a drone strike in Yemen. He cited a leaked 2015 email in which Litt addressed the hostile legislative climate, recommending “keeping our options open” for a change “in the event of a terrorist attack or criminal event where strong encryption can be shown to have hindered law enforcement.”

“Surveillance is ultimately not about safety,” Snowden said. “Surveillance is about power. Surveillance is about control.”

Litt opened his remarks by joking that he could sympathize with the act that went on Ed Sullivan after the Beatles. “I can hear the NSA’s opinion any day,” one student stage-whispered, as he and many others got up to head for the exits. Litt called after them, saying he was “disappointed” with the disdain “given that this is an academic environment.” He then elaborated on the ominous sentiment expressed in his email.

“Every time something bad happens, the finger gets pointed at the intelligence community,” Litt said. “There is a pendulum that swings back and forth, in terms of the public view of the intelligence community, between, ‘You mean you’re doing what?’ and ‘Why didn’t you protect us?’ And that’s a pendulum that’s going to swing again.”

While much of Washington remains hostile to him, Snowden is far more hopeful about Silicon Valley and is increasingly focusing his efforts on influencing technology and the people who make it. “Like me, they grew up with this stuff,” he told me. “They remember what the internet was like before everybody felt it was being watched.”

The Snowden leak “was like a gut punch for people across Silicon Valley,” says Chris Sacca, a venture capitalist who invested early in Twitter and Uber and who now appears on the television show Shark Tank. Sacca was personally friendly with Obama, raising large sums for his 2012 campaign, but was shocked when he discovered the extent of the NSA’s spying and has since become a vocal Snowden supporter. Last November, Sacca did an admiring interview with Snowden at the Summit at Sea, an invite-only weekend of seminar talks and techno dancing aboard a cruise ship, which was attended by the likes of Eric Schmidt, chairman of Alphabet, and Travis Kalanick, CEO of Uber. “After fielding over an hour of tough questions,” Sacca says, “he got a resounding standing ovation from the room.”

Even as Snowden captivated the audience on the boat, though, terrorists were mounting a bloody coordinated attack in Paris. The pendulum was swinging back. At first, Wizner says, Snowden was shaken — he worried that the attacks had wiped out all of his progress. Almost immediately, anonymous security sources blamed encryption for giving cover to the attackers. (Subsequent reports suggest they may have been more reliant on primitive tactics, like using burner phones.) “They dragged out all the old CIA directors, the line of disgrace, to suddenly try to reclaim a halo,” Snowden told me. “It did look really exploitative.” For three weeks, he went quiet, posting just once to Twitter, quoting Nelson Mandela about triumphing over fear. Meanwhile, Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik attacked in San Bernardino, and Trump called for a ban on Muslim immigration.

Wizner advised his client to be patient. Snowden sometimes says he thinks of his existence like a video game: a series of challenges that culminate in a final screen, where you either win or it’s game over. But political outcomes are never so final — it’s an iterative process. In February, when Apple announced it was refusing to break into Farook’s iPhone for the FBI, Snowden was suddenly scoring points again. (“The @FBI is creating a world where citizens rely on #Apple to defend their rights,” he tweeted, “rather than the other way around.”) In an open letter, Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, talked the way Snowden does about privacy, encryption, and government “overreach.” The next day, Snowden spoke at Johns Hopkins University, where hundreds of shivering students lined up to get into a packed auditorium. “This is a case that’s not about San Bernardino at all; it’s not a case that’s about terrorism at all,” Snowden warned. “It’s about the precedent.”

Litt believes that, besides giving information to enemies, Snowden’s disclosures have also had a radicalizing effect in the private sector. “The technology and communications community has moved from a position of willingness to cooperate,” he told me, “to an attitude that ranges from neutrality to outright hostility, which is an extremely bad thing.” Recently, Snowden has been working with technical experts who are mobilizing to fortify the internet’s weak spots, both through collaborations with academic researchers and back-channel conversations with employees at major tech companies.

In all of these conversations, Snowden is operating on the assumption that a truly private space on the internet could be easier to create than to legislate — that it may be more fruitful to coax programmers to invent something that is difficult to hack than it would be to try to reshape the entire national-security bureaucracy so it stops trying. “I’m regularly interacting with some of the most respected technologists and cryptographers in the world,” Snowden said. “I believe that there’s actually a lot more influence that results from those sorts of conversations, because so much of technology is an expert game.”

The aspect of the Snowden leaks that most outraged technology experts was not the NSA’s communications surveillance but its efforts to undermine encryption, which had broad impacts on computer security. That news has “created a period of innovation” in encryption, says Moxie Marlinspike, the San Francisco–based security specialist who developed Signal, the messaging program that Snowden likes to use to communicate. Marlinspike has become friendly with Snowden, whom he met in Moscow, where they had a lengthy discussion about the trade-offs between security and usability. (Snowden is always seeing holes hackers can poke through; Marlinspike wants to make encryption accessible to laypeople.) In April, WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook, announced that it had integrated the Signal protocol Marlinspike developed, allowing it to offer end-to-end encryption. Those sorts of technical decisions, like Apple’s strengthened encryption standards, affect the privacy of millions of customers.

But Snowden is skeptical of the motives of tech companies. “Corporations aren’t friends of the people, corporations are friends of money,” he said. He prefers to collaborate with academics and hacktivists, some of whom are helping him with projects he is developing for the Freedom of the Press Foundation. It already manages SecureDrop, a system for anonymously leaking documents, and the nonprofit’s technical staff is working with Snowden to develop other programs tailored to protect journalists and whistle-blowers. “His goal with us is to start designing and prototyping what the tools of the future will look like,” says Trevor Timm, the foundation’s executive director. One of Snowden’s priorities, unsurprisingly, is improving the security of videoconferencing.

About once a week, the team meets on a beta-stage video platform, where they discuss the painstaking work of testing their technology, a probing process called “dogfooding.” As a prime target for hacking attacks, Snowden is in a unique position to appreciate extreme-threat models. He often comes up with exotic problems to solve and is able to bring in outside minds for confidential consultations. “We’re building small projects,” Snowden says, but he can’t help but see larger applications. He talks enthusiastically about virtual reality, which could soon supplant videoconferencing. “In five years this shit’s going to blow your mind,” Snowden told me. But he also sees potential dangers. “Suddenly, you’ve got every government in the world sitting in every meeting with you.”

Snowden is especially concerned about the monitoring power of Facebook, which acquired Oculus VR, the virtual-reality headset maker, for $2 billion. “What if Facebook has a copy of every memory that you ever made with someone else in these closed spaces?” he asked rhetorically. “We need to have space to ourselves, where nobody’s watching, nobody’s recording what we’re doing, nobody’s analyzing, nobody’s selling our experiences.”

It is clear that in virtual reality, Snowden sees more than just a work tool. “Right now, the technology is not quite there, but this is the first step,” the Snowbot told Peter Diamandis, the space entrepreneur and Singularity University co-founder, in an interview at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show. “I have someone who is very close to me,” Snowden explained, “who was the victim of a serious car accident, and because of that they can’t travel.” Virtual reality could bring them together. Or it could allow him to visit home for Thanksgiving, overcoming what he calls “the tyranny of distance.”

More than one person told me that, after talking to Snowden for hours on end, they got the sense that he is lonely. His conversation is preoccupied with the theme of escape. He recently collaborated on a track with a French musician, delivering a spoken-word monologue on surveillance over an electronic beat, and recommended the title: “Exit.”

Snowden sometimes says that although he lives in Russia, he does not expect to die there, and he told me he is optimistic that he will find a way out, somehow. Maybe some Scandinavian country will offer him asylum. Maybe he can work out some kind of deal — whether outright clemency or a plea bargain — with the Justice Department. Wizner has been working with Plato Cacheris, a well-connected Washington defense attorney, but so far, there have been no official signals that the Justice Department would be willing to offer the kind of lenient terms Snowden would accept. And a window may be closing. He is unlikely to receive a more receptive hearing from Hillary Clinton, who has said he shouldn’t be allowed to return without “facing the music.” As for Donald Trump: He has called Snowden a “total traitor” and suggested he should be executed. “If I’m president,” he predicted last year, “Putin says, ‘Hey, boom — you’re gone.’ ”

So the comparatively thoughtful Obama may be Snowden’s best hope, but even Snowden’s allies concede that they doubt the outgoing president has the inclination to offer a pardon. “There is an element of absurdity to it,” Snowden told me. “More and more, we see the criticisms leveled toward this effort are really more about indignation than they are about concern for real harm.” He says he would return and face the Espionage Act charges if he could argue to a jury that he acted in the public interest, but the law does not currently allow such a defense. “These people have been thinking about the law for so long that they have forgotten that the system is actually about justice,” Snowden said. “They want to throw somebody in prison for the rest of his life for what even people around the White House now are recognizing our country needed to talk about.”

Earlier this year, Snowden was buoyed by an invitation from an unexpected source. David Axelrod, the president’s former top political strategist, asked him to appear at the institute he now runs at the University of Chicago. Beforehand, they had a video chat. “The president of the United States’ closest advisers,” Snowden told me later, “are now introducing me and sharing the stage with me in ways that aren’t actually critical. I’m not saying this to build myself up. I’m talking about the recognition by even the people who have the largest incentives to delegitimize me as a person, that maybe we overreacted, maybe this is a legitimate conversation that we need to have.”

Axelrod asked Geoffrey Stone, a liberal law professor who is friendly with Obama, to moderate the public talk. Stone is a member of the ACLU’s National Advisory Council and the author of a book titled Top Secret: When Our Government Keeps Us in the Dark, but he also served on Obama’s commission to review the NSA’s surveillance programs, an experience that gave him access to classified information and a dim view of Snowden. “My view is that he cannot be granted clemency, because he did commit a criminal offense and it did considerable harm,” Stone told me. “The people who are celebrating Snowden have no understanding of the harm, for the reason that the people in the intelligence world can’t really explain the harm to them.” Snowden considered Stone’s position to be “an example of regulatory capture,” proof of the seductive power of security clearances. Secret knowledge, Snowden says, “is a very intoxicating thing.”

Still, Snowden was looking forward to the debate, if only because it illustrates his progress. Wizner, who considered the Axelrod relationship important to his future clemency push, attended the May event in person. “We’ve gone from the president saying ‘We’re not going to scramble jets for a 29-year-old hacker’ to talking with the president’s rabbi,’ ” Wizner said backstage as event staff set up computers and projection equipment. “That’s a good journey for us.”

Axelrod shambled in, looking sleepy-eyed as always, as students filled the auditorium and Wizner texted last-minute instructions to his client over Signal. “Whatever you think about Edward Snowden and his actions, and the adjectives range from traitor to hero,” Axelrod said by way of introduction, “he has indisputably triggered a really vital public debate about how we strike a balance between civil liberties and security.” He sat down in the front row as Snowden’s bashful grin filled a large screen.

Snowden had already done one event that day, a cybersecurity conference in Zurich, and he seemed weary as Stone probed for logical weaknesses. The law professor asked when it was appropriate for “a relatively low-level official in the national-security realm to take it upon himself to decide that it is in the national interest to disclose the existence of programs that have been approved … To decide for himself that ‘I think they’re wrong.’ ” Snowden gave his usual homilies about the Constitution, whistle-blowing, and civil disobedience. “Do we want to create a precedent that dissidents should be volunteering themselves not for the 11 days in jail of Martin Luther King or the single night of Thoreau,” he asked, “but 30 years or more in prison, for what is an act of public service?”

Stone pointed out that Congress could pass a law allowing defendants to make a whistle-blowing defense in Espionage Act cases but shows no signs of doing it. “You believe in democracy,” Stone said. “But democracy doesn’t agree with you.” The professor jabbed and Snowden weaved, setting his jaw and taking swigs from a big plastic water bottle. But when the floor opened for questions, it was clear who had won the audience. One student after another got up to offer Snowden praise.

“Did you expect to become a celebrity in this way?” one asked.

“If you go back to June 2013,” Snowden said, “I said, ‘Look, guys, stop talking about me, talk about the NSA.’ ” But he added, “Our biology, our brains, the way we relate to things, is about character stories. So they simply would not let me go.”

Axelrod watched impassively, his fingers tented under his nose. The full effect of Snowden’s performance did not become clear until a few weeks later, when Axelrod had Eric Holder — the former attorney general, once Snowden’s chief pursuer — on his podcast, The Axe Files. Holder allowed that Snowden “actually performed a public service,” while Axelrod calmly presented Snowden’s arguments.

“I think there has to be a consequence for what he has done,” Holder replied. “But I think, you know, in deciding what an appropriate sentence should be, I think a judge could take into account the usefulness of having had that national debate.”

Holder’s concession made international headlines. It didn’t mean anything legally, but symbolically it spoke volumes. Political realities were starting to come into alignment with Snowden’s virtual ones. From his computer in Moscow, Snowden tweeted:

2013: It’s treason!

2014: Maybe not, but it was reckless

2015: Still, technically it was unlawful

2016: It was a public service but

2017:

*This article appears in the June 27, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.