According to legend, Colorado’s Cheyenne Mountain is a sleeping dragon that many years ago saved the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. In the Native American story, the Great Spirit punished the people by sending a massive flood, but after they repented, it sent a dragon to drink the water away. The dragon, engorged by the massive amount of water, fell asleep, was petrified and then became the mountain. Unlike the dragon of legend, the Cheyenne Mountain Complex has never slept during 50 years of operations. Since being declared fully operational in April 1966, the installation has played a vital role in the Department of Defense during both peacetime and wartime. (U.S. Air Force Video edited by Travis Burcham // Video shot by Andrew Arthur Breese)

According to legend, Colorado’s Cheyenne Mountain is a sleeping dragon that many years ago saved the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. In the Native American story, the Great Spirit punished the people by sending a massive flood, but after they repented, it sent a dragon to drink the water away. The dragon, engorged by the massive amount of water, fell asleep, was petrified and then became the mountain.

Unlike the dragon of legend, the Cheyenne Mountain Complex has never slept during 50 years of operations. Since being declared fully operational in April 1966, the installation has played a vital role in the Department of Defense during both peacetime and wartime.

The Cheyenne Mountain Complex is a military installation and nuclear bunker located in Colorado Springs, Colorado at the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station. The mountain itself is about 9,500 feet tall, and the tunnel entrance sits about 2,000 feet from the top.

Though the complex may have changed names during the past five decades, its mission has never strayed from defending the U.S. and its allies. Today, it is known as Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station, with a primary role of collecting information from satellites and ground-based sensors throughout the world and disseminating the data to North American Aerospace Defense Command, U.S. Northern Command and U.S. Strategic Command — a process Steven Rose, Cheyenne Mountain AFS deputy director, compares to the work done by the stem of the human brain.

“Those sensors are your nerves out there sensing that information,” Rose said, “but the nerves all come back to one spot in the human body, together in the brain stem, entangled in a coherent piece. We are the brain stem that’s pulling it all together, correlating it, making sense of it, and passing it up to the brain — whether it’s the commander at NORAD, NORTHCOM or STRATCOM — for someone to make a decision on what that means. That is the most critical part of the nervous system and the most vulnerable. Cheyenne Mountain provides that shield around that single place where all of that correlation and data comes into.”

Cheyenne Mountain Complex is a military installation and nuclear bunker located at the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

In the 1950s, the DOD decided to build the installation as a command and control center defense against long-range Soviet bombers. As the “brain stem,” it would be one of the first installations on the enemy’s target list, so it was built to withstand a direct nuclear attack.

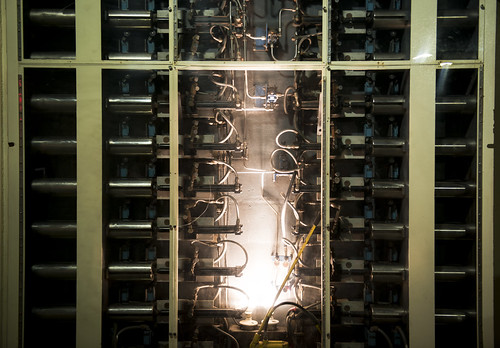

Cheyenne Mountain’s 15 buildings rest on more than 1,300 springs, 18 inches from the mountain’s rock walls, so they could move independently in the event of a nuclear blast and the inherent seismic event. In addition, an EMP, being a natural component of a nuclear blast, was already considered in Cheyenne Mountain’s original design and construction features, Rose said.

The Cheyenne Mountain Complex is a military installation and nuclear bunker located at the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Its entrance is equipped with two 23-ton blast doors and the mountain has a facility with 15 buildings that rest on more than 1,300 springs, 18 inches from the mountain’s rock walls so they could move independently in the event of a nuclear blast or earthquake.

“Back then, it was just part of the effect of a nuclear blast that we were designed for at Cheyenne Mountain,” he added. “If you fast forward 50 years from our construction, the EMP threat has become more important to today’s society because of the investment that has been made into electronics. Just by sheer coincidence, since we were designed in the 50s and 60s for a nuclear blast and its EMP component, we are sitting here today as the number one rated EMP protected facility. The uniqueness of the mountain is that the entire installation is surrounded by granite, which is a natural EMP shield.”

The station, built 7,000 feet above sea level, opened as the NORAD Combat Operations Center. When NORAD and the newly stood up NORTHCOM moved their main command center to Peterson Air Force Base in 2008, many believed Cheyenne Mountain had closed. Today, Cheyenne Mountain hosts an alternate command center for NORAD and is landlord to more than a dozen DOD agencies, such as the Defense Intelligence Agency.

“When I bring official visitors up here, not only are they surprised that we’re still open,” said Colonel Gary Cornn, Cheyenne Mountain AFS Installation Commander. “Many are impressed by the original construction, the blasting of the tunnels, how the buildings are constructed inside, and some of the things we show them, such as the survivability and capability we have in the blast valves, the springs, the way we do our air in the Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC) filtering and the huge blast doors. It’s funny to see senior officers and civilians become sort of amazed like little kids again.”

The two 23-ton blast doors at the entrance inside the Cheyenne Mountain Complex are made of steel and can take up to 20 seconds to close with the assistance of hydraulics. If the hydraulics were to fail, the military guards stationed in the tunnel can close the doors in 40 seconds.

The threats and sources have drastically changed from when the station opened at the height of the Cold War, but the station’s iconic 25-ton steel doors remain the same, ready to seal the mountain in 40 seconds to protect it from any threat. The underground city beneath 2,000 feet of granite still provides the protection to keep the station relevant as it begins its next half-century as “America’s Fortress.”

Longtime Cheyenne Mountain employees like Rose and Russell Mullins, the 721st Communications Squadron deputy director, call themselves “mountain men.” Mullins’ time in the mountain goes back to the Cold War era, about halfway through its history to 1984.

Although the Soviet Union’s nuclear arsenal was the main focus, today’s Airmen conduct essentially the same mission: detect and track incoming threats to the United States; however, the points of origin for those threats have multiplied and are not as clearly defined.

Senior Airman Ricardo Collie, a 721st Security Forces member, patrols the north gate of the Cheyenne Mountain Complex at Cheyenne Air Force Station, Colorado. Collie is one of many security layers to enter more than a mile inside a Colorado mountain to a complex of steel buildings that sit in caves.

“The tension in here wasn’t high from what might happen,” Mullins said. “The tension was high to be sure you could always detect (a missile launch). We didn’t dwell on the fact that the Soviet Union was the big enemy. We dwelled on the fact that we could detect anything they could throw at us.

“There was a little bit of stress back then, but that hasn’t changed. I would say the stress now is just as great as during the Cold War, but the stress today is the great unknown.”

The 9/11 attacks added another mission to NORAD and the Cheyenne Mountain Directorate – the monitoring of the U.S. and Canadian interior air space. They stand ready to assist the Federal Aviation Administration and Navigation Canada to respond to threats from the air within the continental U.S. and Canada.

Airplane icons blot out most of the national map on the NORAD/NORTHCOM Battle Cab Traffic Situation Display in the alternate command center. To the right another screen shows the Washington, D.C., area, called the Special Flight Restrictions Area, which was also added after 9/11.

Tech. Sgts. Alex Gaviria and Sarah Haydon, both senior system controllers, answer phone calls inside the 721st Communications Squadron Systems Center in the Cheyenne Mountain Complex. The systems center monitors around the world for support and missile warning.

Whenever a crisis would affect NORAD’s vulnerability or ability to operate, the commander would move his command center and advisors to the Battle Cab, said Lt. Col. Tim Schwamb, the Cheyenne Mountain AFS branch chief for NORAD/NORTHCOM.

“I would say that on any given day, the operations center would be a center of controlled chaos; where many different things may be happening at once,” Schwamb said. “We’re all trying to ensure that we’re taking care of whatever threat may be presenting itself in as short an amount of time as possible.

“I would describe it as the nerve center of our homeland defense operations. This is where the best minds in NORAD and U.S. Northern Command are, so that we can see, predict, and counter any threats that would happen to the homeland and North American region. It’s really a room full of systems that we monitor throughout the day, 24-hours a day, seven-days a week, that give us the information to help us accomplish the mission.”

Protecting America’s Fortress is a responsibility that falls to a group of firefighters and security forces members, but fighting fires and guarding such a valuable asset in a mountain presents challenges quite different from any other Air Force base, said Matthew Backeberg, a 721st Civil Engineer Squadron supervisor firefighter. Firefighters train on high-angle rescues because of the mountain’s unique environment, but even the most common fire can be especially challenging.

Kenny Geates and Eric Skinner, both firefighters with Cheyenne Mountain’s Fire and Emergency Services Flight, put out a simulated fire in an area underneath the facility during an exercise. With no room to drive throughout the facility to reach the fires, firefighters have to run to them.

“Cheyenne Mountain is unique in that we have super challenges as far as ventilation, smoke and occupancy,” Backeberg said. “In a normal building, you pull the fire alarm, and the people are able to leave. Inside the mountain, if you pull the fire alarm, the people are depending on me to tell them a safer route to get out.

“If a fire happens inside (the mountain), we pretty much have to take care of it,” Backeberg added. “We’re dependent on our counterparts in the CE world to help us ventilate the facility, keep the fire going in the direction we want it to go, and allow the occupants of the building to get to a safe location – outside the half mile long tunnel.”

Although Cheyenne Mountain, the site of movies and television series such as “WarGames,” “Interstellar,” “Stargate SG-1” and “Terminator,” attracts occasional trespassers and protesters, security forces members more often chase away photographers, said Senior Airman Ricardo Pierre Collie, a 721st Security Forces Squadron member.

“The biggest part of security forces’ day is spent responding to alarms and getting accustomed to not seeing the sun on a 12-hour shift when working inside the mountain,” Collie said.

Steven Rose (left), the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station deputy director, and the safety chief paddle a boat toward the back of one of Cheyenne Mountain Complex’s underground reservoirs to place a floating device. The underground reservoirs carved from solid rock provide drinking and cooling water, while a lake of diesel fuel sits ready for the six locomotive-sized diesel generators capable of powering a small city.

Security forces must also be ready to respond at a moment’s notice because, when charged with protecting an installation like Cheyenne Mountain AFS, the reaction time is even more crucial. Airmen like Collie feel their responsibly to protect America’s Fortress remains as vital today as it was during the Cold War.

“The important day at Cheyenne Mountain wasn’t the day we opened in 1966,” Rose said. “The next important date isn’t in April 2016 (the installation’s 50-year anniversary), it’s about all those days in between. The Airmen who come here to Cheyenne Mountain every day will be watching your skies and shores in (the nation’s) defense.”

As Cheyenne Mountain AFS enters its next 50 years, the dragon remains awake and alert to all threats against the U.S.