One thing sits at the heart of what many consider a surveillance state within the US today.

The problem does not begin with political systems that discourage transparency or technologies that can intercept everyday communications without notice. Like everything else in Washington, there’s a legal basis for what many believe is extreme government overreach—in this case, it's Executive Order 12333, issued in 1981.

“12333 is used to target foreigners abroad, and collection happens outside the US," whistleblower John Tye, a former State Department official, told Ars recently. "My complaint is not that they’re using it to target Americans, my complaint is that the volume of incidental collection on US persons is unconstitutional.”

The document, known in government circles as "twelve triple three," gives incredible leeway to intelligence agencies sweeping up vast quantities of Americans' data. That data ranges from e-mail content to Facebook messages, from Skype chats to practically anything that passes over the Internet on an incidental basis. In other words, EO 12333 protects the tangential collection of Americans' data even when Americans aren't specifically targeted—otherwise it would be forbidden under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978.

In a May 2014 interview with NBC, former NSA contractor Edward Snowden said that he specifically asked his colleagues at the NSA whether an executive order could override existing statutes. (They said it could not.) Snowden’s lawyer, Jesselyn Radack, told Ars that her client was specifically “referring to EO 12333.”

EO 12333, section 2.3 paragraph

2.3 Collection of Information. Agencies within the Intelligence Community are authorized to collect, retain, or disseminate information concerning United States persons only in accordance with procedures established by the head of the agency concerned and approved by the Attorney General, consistent with the authorities provided by Part 1 of this Order. Those procedures shall permit collection, retention, and dissemination of the following types of information:(a) Information that is publicly available or collected with the consent of the person concerned;

(b) Information constituting foreign intelligence or counterintelligence, including such information concerning corporations or other commercial organizations. Collection within the United States of foreign intelligence not otherwise obtainable shall be undertaken by the FBI or, when significant foreign intelligence is sought, by other authorized agencies of the Intelligence Community, provided that no foreign intelligence collection by such agencies may be undertaken for the purpose of acquiring information concerning the domestic activities of United States persons;

(c) Information obtained in the course of a lawful foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, international narcotics or international terrorism investigation;

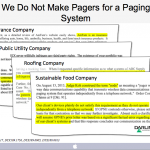

“This program was started at least back in 2001 and has expanded to between 80 and 100 tap points on the fiber optic lines in the lower 48 states,” he said by e-mail. “Most of these fiber optic tap points are not on the East or West coast. This means that the primary target of this collection is domestic... Most collection of US domestic communications and data is done under EO 12333, section 2.3 paragraph C in the Upstream program. They claim, near as I can tell, that all domestic collection is incidental. That’s, of course, the vast majority of data.”

Specifically, that subsection allows the intelligence community to "collect, retain, or disseminate information concerning United States persons" if that information is "obtained in the course of a lawful foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, international narcotics or international terrorism investigation."'

The path to EO 12333

Executive orders vary widely. One of the most famous executive orders, the Emancipation Proclamation, freed slaves in the United States under President Abraham Lincoln. A more infamous example came under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who issued an executive order to intern Japanese-Americans in prison camps in 1942.

President Ronald Reagan signed EO 12333 within his first year in office, 1981, largely as a response to the perceived weakening of the American intelligence apparatus by his two immediate predecessors, Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter. Later, EO 12333 was amended three times by President George W. Bush between 2003 and 2008.

“Reagan did this at every opportunity: with military exercises, challenging the Soviets in their own airspace and waters, across the board. The gloves were coming off,” Melvin Goodman told Ars. Goodman was the CIA's division chief and senior analyst at the Office of Soviet Affairs from 1976 to 1986. He’s now the director of the National Security Project at the Center for International Policy in Washington, DC.

Bush's reasons for strengthening EO 12333 were similar. After the United States faced another existential threat in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Bush—and later President Barack Obama—used EO 12333 to expand American surveillance power. But if EO 12333 is essentially a reaction, how was mass surveillance handled beforehand?

Further Reading

In the 1960s, the American intelligence community turned its spy gear and covert capabilities against its own people by infiltrating and disrupting various civil rights groups (COINTELPRO), by capturing mail and telegrams (Project Shamrock), monitoring the activities of Americans abroad (Operation Chaos), and by intercepting electronic communications of many high-profile Americans (Project Minaret). Such targets included Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali, and even antiwar activist and actress Jane Fonda.

By 1975, the US Senate’s Church Committee started exposing those programs, and many notable intelligence reforms soon took shape—including FISA and the corresponding Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC). Following the intelligence abuses during the Nixon era, new president Gerald Ford set about to change the way the NSA and other intelligence agencies did business.

In 1976, President Ford issued Executive Order 11905, which restricted much of this activity and put in rules like these:

(b) Restrictions on Collection. Foreign intelligence agencies shall not engage in any of the following activities:

(1) Physical surveillance directed against a United States person, unless it is a lawful surveillance conducted pursuant to procedures approved by the head of the foreign intelligence agency and directed against any of the following:

(i) A present or former employee of such agency, its present or former contractors or their present or former employees, for the purpose of protecting foreign, intelligence or counterintelligence sources or methods or national security information from unauthorized disclosure; or

(ii) a United States person, who is in contact with either such a present or former contractor or employee or with a non-United States person who is the subject of a foreign intelligence or counterintelligence inquiry, but only to the extent necessary to identify such United States person; or

(iii) a United States person outside the United States who is reasonably believed to be acting on behalf of a foreign power or engaging in international terrorist or narcotics activities or activities threatening the national security.

(2) Electronic surveillance to intercept a communication which is made from, or is intended by the sender to be received in, the United States, or directed against United States persons abroad, except lawful electronic surveillance under procedures approved by the Attorney General; provided, that the Central Intelligence Agency shall not perform electronic surveillance within the United States, except for the purpose of testing equipment under procedures approved by the Attorney General consistent with law.

Notably, Ford (and later Carter under Executive Order 12036) made it far more difficult for the US government to monitor its own people. By contrast, today EO 12333 specifically allows for broad “incidental collection” that may include US citizens. More specifically, EO 12333 allows for "information obtained in the course of a lawful foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, international narcotics, or international terrorism investigation.” The push toward this reality started in the early '80s.

"It is not so much that new powers were given to the NSA as it was a matter of showing that the NSA would not be addressed as explicitly in 12333, thereby signaling that the NSA would have more elbow room to use its own discretion in moving forward," Loch Johnson, a professor of international affairs at the University of Georgia, told Ars. "This signaling was achieved by removing Carter's more detailed language about that agency. This removal of language indicates a lifting of close attention to the specifics of NSA activities—a subtle grant of permissiveness, not so much in explicit language as in the absence of as many explicit prohibitions."

“The Reagan Administration supports an aggressive and effective intelligence effort.”

In fact, a March 1981 letter from William Casey, the director of Central Intelligence and the head of the CIA to one of Reagan’s national security advisors, suggests that the Reagan administration was also well aware of the abuses conducted under its predecessors. (Ars obtained this document from Kenneth Mayer, who obtained it from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.) Despite this, Reagan advisors ultimately seemed more concerned with the perception of wrongdoing rather than actual wrongdoing.

“The absence of clear-cut, Presidentially directed restrictions will, in my judgment, create enormous uncertainty among the operators; it will reopen the wounds of the 1970s in which many intelligence officers thought of themselves as potential Felts and Millers,” Casey wrote.

(Mark Felt was the number two at the FBI under Nixon, and more than 20 years later he admitted that he was the famous “Deep Throat” leaker. Miller refers to a top Justice Department lawyer, Herbert Miller, a longtime Nixon ally.)

Casey continued:

Furthermore, the inevitable media campaign which would ensure under an Order devoid of any guidelines or restrictions, with likely charges that the Intelligence Community or the Administration intends to expand collection concerning the domestic activities of United States persons, will necessarily have an impact on the attitudes of our operators.

…Of greater significance, however, is the impact that accusations of CIA intrusive domestic activity, no matter how irrational, will have on the effectiveness of our operators. It seems clear to me that an environment in which the Intelligence Community is under drumfire political attack is not conducive to gaining the cooperation of Americans at home and abroad.

He concluded, "I do heartily agree with you, however, that the most significant goal to be accomplished by the promulgation of a new Executive Order is to send a clear signal to the Intelligence Community and to the National that the Reagan Administration supports an aggressive and effective intelligence effort."

In another memo from Casey to Edwin Meese, then a presidential advisor (who later became attorney general during Reagan’s second term), Casey refers to the administration's desire to rebuild the intelligence community.

“What is not widely understood is that many of the most onerous impediments came from the sheer size and complexity of implementing regulations imposed by the Justice Department during the Ford and Carter years,” Casey wrote. “These caused operatives in the field to throw up their hands and quit trying. The Executive Order is needed as a road map to chart simply what they can and can’t do.”

You must login or create an account to comment.