In Defense Of Killer Robots

The United Nations will soon gather to ponder the most critical question of our time: What do we do about the proliferation of lethal automatons — otherwise known as “killer robots.”

These androids robots, yet to be invented, will have the ability to target people without “direct human mediation,” a technological advancement that is attracting the predictable pushback. As the Washington Post reports, groups like Human Rights Watch — which recently released a chilling report called “Shaking the Foundation: The Human Implications of Killer Robots” — and dignitaries, from Desmond Tutu to Lech Walesa, have signed a letter asserting that it is “unconscionable that human beings are expanding research and development of lethal machines that would be able to kill people without human intervention.”

Why is that? Because human beings have a long history of making rational and ethical decisions when it comes to killing people?

Alas, the United States military has already issued a directive prohibiting lethal autonomous robots. The question is why? Why are we so afraid of robots in general, and why can’t we have robots do our dirty work? Human mediation, as anyone who’s interacted with humans understands, is typically messy and irrational. Why would it be less likely for a robot to comply with international humanitarian law than a human? Why is it morally acceptable to firebomb a city or create ‘shock and awe’ in an entire country with the aid human interaction but ethically unacceptable to send a programmable machine to decimate the enemy — and only the enemy — saving the lives and limbs of hundreds or thousands of Americans soldiers? There is, of course, a legitimate debate about how we deploy drones, but we should be focusing on ways technological advancements in unmanned combat can help mitigated collateral damage.

I’m not an expert on nonexistent military technology, but here are a few things that are likely true about “killer robots”:

They will not be break down in the chaos and confusion of war. They won’t lose their moral bearings under duress. Though it is true that robots never ignore orders, even unethical orders, they also won’t surrender to vengeance, anger or fear – or the enemy. Robots will not walk off and join the Taliban in the middle of the night. Soldiers kill because they are ordered to, and sometimes because they feel threatened and occasionally by accident, but robots do not. Robots don’t need to fire into crowds to subdue mobs, they don’t panic and they don’t make too many mistakes. If they perform their job, in fact, there is a good chance that we would see less war and less death because, well, who wants to fight a robot army?

Let’s also dismiss some other concerns of anti-robot crowd: The idea that less hands-on killing makes society more depraved is not borne out. As we have become less personally involved in warfare we have continued to be less violent, as well. (Read Steven Pinker’s masterful “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined.”) And as to the question of who will be responsible when an innocent is killed by a robot, that’s easy: The institution or leaders who send a machine to kill. We will be no less culpable for our actions because we deploy metal surrogates rather than ones made of flesh and bones.

Who knows? Perhaps, in the far flung future, robots will able to make some ethical choices on their own — with even better results than humans. The Office of Naval Research has already awarded $7.5 million in grants to researchers at Brown, Georgetown, RPI, Tufts and Yale to study the possibilities of teaching robots the difference between right and wrong and the weight of moral consequences. Can a robot ever have a simulated “soul” that allows it to feel empathy, or utilize intuitive skills or deal with ethical dilemmas? Yes. But when that happens we will be in singularity and engaged in a deeper philosophical discussion. If our robot overlords permit it.

Softbank recently introduced a human-like robot named “Pepper” which is purportedly the first android to have human feelings. According to the company’s CEO “the robot that makes its own decision to act with love” and will have the ability to read and express emotions. This is just code, of course, but if it can supplement the work of medical worker, or give some companionship, or be a babysitter, or entertain the elderly, what’s the problem?

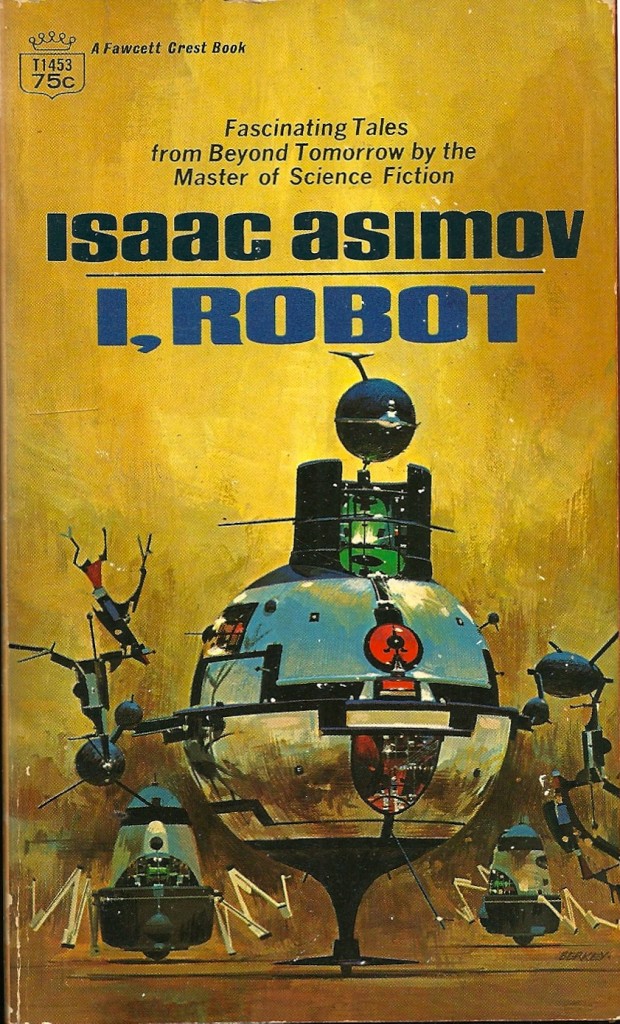

But rather than an artificial computer-driven moral compass, researchers should be more interested in outfitting robots with a rarer human quality: rationality. It seems that we have an illogical anxiety about technology, especially automation. Part of it misguided economic fears. Part of it is certainly cultural— from Isaac Asimov to 2001 to The Terminator — as cyborgs typically portend some dystopian future punctuated by a robot-slave rebellion rather than the boring reality: machines make our lives more efficient, productive, easier and fulfilling. And they will soon be driving us to work. There’s nothing scary about it.

You may remember on his recent trip to Japan, Barack Obama, who has more than once lamented the rise of the ATM, played a bit of soccer — or what he might call “football” — with Honda’s humanoid robot ASIMO: “I have to say the robots were a little scary,” said our technophobic president, “They were too life-like.”

This is common. In a recent survey by the Pew Research Center and Smithsonian Magazine, Americans were asked about a wide range of conceivable scientific developments in robotics, bioengineering and beyond. Broadly speaking, people consider themselves technological optimists over pessimists. But when you bore down into the specifics they quickly became barbarians.

Pew, for example, found that 66 percent of prospective (abusive) parents believe the world would be a worse place if they could alter the DNA of their children to make them smarter, healthier or more athletic. Proactively curing cancer or allowing your child a life free of pain and suffering from some disease seems like a no-brainer to me, but I’m a techno-utopian, I guess. Another 53 percent of Americans think it would be a change for the worse if most people wore implants or other devices that fed them information about the world around them.

When it comes to robots, 65 percent believe it would be a change for the worse if lifelike robots become the caregivers for the elderly and people in poor health and 63 percent think it would be a change for the worse if personal and commercial robotic drones were given permission to fly through most U.S. airspace.

This is unfortunate. For starters, dismissing drones is just ridiculous. They are incredibly useful in ways that go beyond being blowing up a terrorist. And, as long as we have to fight there is absolutely no reason why we shouldn’t have our best technology doing the fighting for us.